The ballet of work

Museum items – for 20 years (2)

By Christoph Pinzl

Anyone who talks to old hop farmers may notice that their stories are a little different from what you might expect. You hardly ever hear them talk about the proverbial “good old days,” how everything used to be better, how wonderful times were, how life was so much more worth living, etc., etc. At least when it comes to the various autumn and spring tasks that hop farming demanded. In the past, everything was done exclusively by hand. Uncovering, cutting, hanging wire, twisting, cleaning, plowing, harrowing, cultivating, fertilizing, just to name the most important ones. For uncovering, the manual removal of soil from the sticks with a riding hoe, we calculated the almost unbelievable figure of 70 tons of soil moved – in a single day, mind you! A hop farmer once described twisting the vines onto the wire as “the thousandfold kneeling of the hops.” Like in church, pure humility, combined with a little pain. The hunching over when cutting the sticks, hanging up wire with a seven-meter-long pole, your head tilted back for hours, your eyes fixed on the sun, plowing and harrowing with skittish horses or stubborn oxen that tear down the vines with their horns, tightening wire in the winter cold with numb fingers, hauling manure with a dung cart, spreading it with a pitchfork – none of it exactly something to write home about.

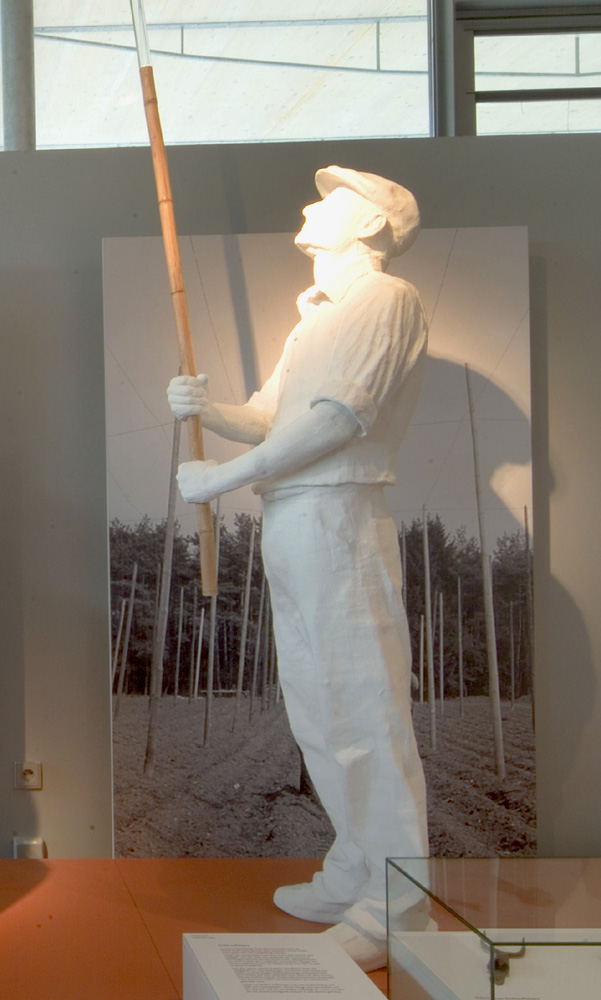

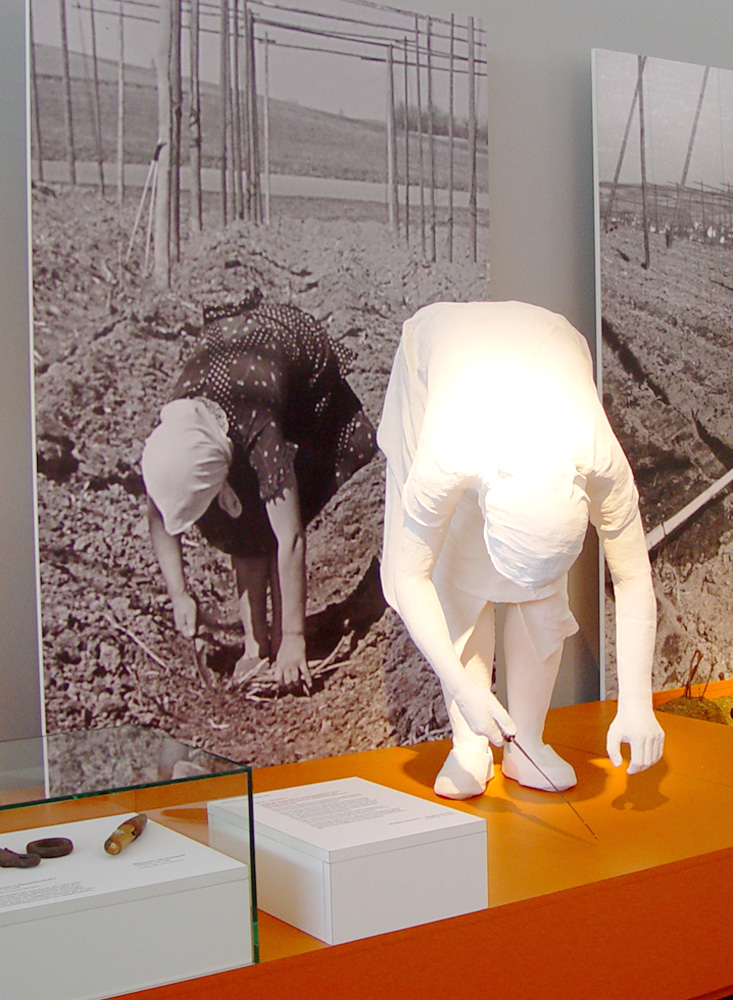

When planning our museum exhibition, we soon realized that the tools used for these tasks—riding axes, carving knives, hanging poles, plows, harrows—were far too plain, far too functional for the work they once had to do. A rusty knife with a wooden handle, a long-handled hoe, and a bamboo pole say little about how strenuous it was to use them. So the decision was made: there should be figures here. Some museums furnish their entire permanent exhibition with figures. We didn’t want to go that far. But here, figurines, as they are technically called, had their clear justification.

However, every museum designer is then faced with the same problem: how realistic should the figures be and how much should be abstracted? The main problem is always the facial expression. Emotional and expressive like in a Renaissance painting? That always overshoots the mark and never hits the heart of the matter. Or sober and stylized like a mannequin? Those who have no money at all in museums get hold of a few discarded ones. And mainly produce laughter.

The solution lay somewhere in between. Munich artist Afra Dopfer and South Tyrolean sculptor Michael Schrattenthaler had the brilliant idea. We already knew Afra Dopfer; she once designed the famous “Handmännchen” (little hand men) for the Wolnzacher Museum der Hand. This time, the two wanted to cast each figure life-size from real people, “using plaster bandages in the appropriate posture for the activity,” as stated in the contract with the artists at the time. “A wooden frame is inserted into the hollow plaster mold for stabilization, as well as a means of attachment to the floor or base. The figure is dressed in original clothing (based on a model), including a hat, etc. The clothing is stiffened and arranged in natural-looking folds. The entire figure is reworked with plaster to achieve a uniform overall surface and painted white. Since these are casts of real people, the proportions and posture of the figures are absolutely “naturalistic.” This naturalism is broken up somewhat by the details being toned down slightly through the slightly simplifying surface of the plaster bandages.” So says the service specification. The extent to which the brave models for the plaster figures received a share of the (modest) artist’s fee is not known. In retrospect, one can only pay the highest respect to these poor people. They suffered for our museum. Seriously. Where the real workers could at least stand up from a squatting position, look straight ahead again, or straighten their crooked backs, the actors had to remain motionless for at least half an hour, with straws in their noses. In the end, the scaffolding must have hurt them at least as much as it hurt the hop workers they were portraying. Unfortunately, there are no more recordings of the creative process.

When the figures finally rested expressively in their frozen poses in the museum, the appropriate name was quickly decided: Arbeitsballett (Work Ballet). Exhausting, laborious, the result of endless, monotonous practice. And yet expressive, powerful, dynamic, full of pride in their own skills and achievements.

Each individual figure’s position relates to the others, in contact with them. Like in a rehearsed choreography. Even 20 years later, we are still enthusiastic. We are also delighted by the condition of the figures after being viewed by thousands of visitors over the years.

They stand there completely free, without the protection of glass or sufficient distance, just on a low museum pedestal, even though they are made of fragile plaster and the white paint is not exactly ideal for dirty hands. This was a conscious decision. Display cases create distance, coolness, and austerity, but we wanted to bring the old days to life as much as possible. So far, everything has gone well. The figures are hardly ever touched, serve as little more than background decoration for more or less amusing selfies, and do not have to endure curious tests of their fragility. Perhaps they simply command the respect they deserve from every viewer. For the figures as works of art. And for the people who once had to perform the ballet of work in everyday hop farming.