The coldest place in Germany

The Hop Research Institute in Hüll near Wolnzach holds the cold record

By Christoph Pinzl

Nowadays, when the thermometer drops below freezing, public excitement rises proportionally. Climate change, combined with constant real-time information via weather apps, makes this possible. One wonders how people managed in the past, when it was supposedly much colder. It’s all hard to believe. Then it usually doesn’t take long before the story of the ultimate cold record is brought up again. Once upon a time on Christmas Eve (a warning sign for the new millennium…?), in the Berchtesgaden Alps, at Funtensee in the Steinernes Meer, a measuring device installed there stopped at minus 45.9°C on December 24, 2001. Definitely very cold, no doubt about it. Marmots are particularly trusting there, from first-hand experience, perhaps their flight instincts are permanently frozen, who knows. Responsible for the polar temperatures at the idyllically situated mountain lake is its very special basin location, without wind movement, without sunshine, without above-ground water drainage and much more.

That is precisely why this record is considered by the German Weather Service to be worthless. Zero representative, say the meteorologists. There are probably even colder spots somewhere in the Alps, but there are no measuring devices there. This says nothing about conditions in Germany.

The official record low can therefore continue to be held by another place, in the middle of the tertiary hill country of Upper Bavaria, where people live, work, and even conduct research: Hüll near Wolnzach, in the center of the world’s largest hop-growing region, the Hallertau. And it has been for a very long time. On February 12, 1929, a frosty minus 37.8°C was measured there.

Hüll Hop Research Institute, around 1935.

The Institute for Hop Research, then still called the Hans Pfülf Institute after the former director of the Munich Pschorr Brewery, had been located in Hüll since 1926. A consortium of brewers, hop traders, hop growers, and government agencies had established the research center in response to the catastrophic infestation of hops by the fungal disease Peronospora. With the help of precise scientific findings, they wanted to arm themselves against future threats from such devastating plant diseases. They wanted to know how well which varieties resisted which infestations, what role soil conditions played in this, what care measures were needed for the hop plant, the cultivation techniques, the trellis forms, and harvest times. They wanted to breed new, more stable varieties, find better techniques, and understand how all the factors were connected and influenced each other. This was a systems approach that was very modern and innovative for its time.

In addition, the researchers in Hüll did not want to stop at theory, but wanted to spread the new knowledge among the people, inform and train the hop growers, and show them how to use the new, unfamiliar pesticides and sprayers correctly.

And, of course, they wanted to know what influence the climate had on this complex system. Immediately after the institute was founded, a meteorological station was set up in Hüll, a “second-order station” as it was called, referring to the technical equipment of the station. Every day, data on temperature, precipitation, sunshine duration, humidity, and wind were recorded there. Of course, the data during the hop growth phase, i.e., between April and September, was particularly important to the researchers. But even in winter, meticulous records were kept of all climatic conditions in the middle of the Hallertau growing region.

And so it came to pass that on February 12, 1929, the Hüll thermometer read minus 37.8°C. The hop vines themselves seemed little affected by these polar temperatures, quite the contrary in fact. In 1929, the hops developed excellently, and the late summer harvest was better than it had been for a long time. In fact, it was too good, because prices on the saturated hop market subsequently plummeted, but that’s another story. And it is doubtful whether the brutal winter frost had anything to do with it.

The Hüll climate station in its early days, 1927.

Unfortunately, there are no detailed records of how the temperature on that February day in 1929 felt to the people in the area. They certainly had more to contend with than their hop plants, even if icy windshields and delayed regional trains were not the most pressing problems at the time.

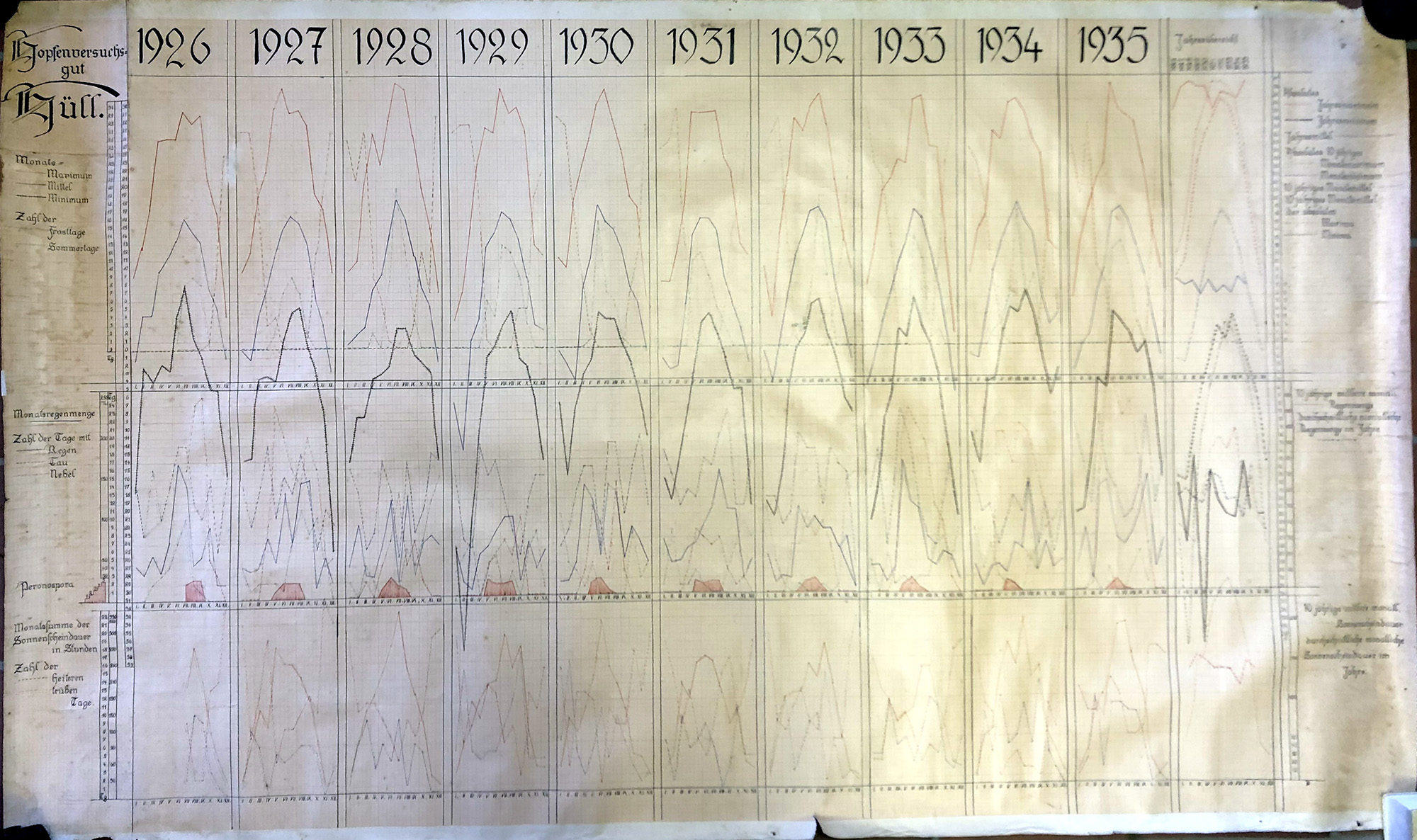

However, it is possible that people were not quite as surprised as we are today when we experience much milder frost conditions. Our museum’s collection includes an old hand-drawn display board on which the Hüll researchers recorded their climate data between 1926 and 1935. The extreme temperature swing in February 1929 is clearly visible there. However, it also shows that double-digit sub-zero temperatures, even below minus 20°, were the rule rather than the exception in winter. So perhaps the temperature record did not impress the people of Hallertau as much as one might think. Whether it’s minus 20 or minus 30 doesn’t really matter. Many people probably didn’t even notice the record due to the lack of weather reports on television, let alone wetteronline.de. Due to today’s climate change, it is probably a record for eternity.

Board with climate data from the Hüll Hop Research Institute, 1926-1935. The dip in the cold record in 1929 is clearly visible.

To be completely honest, the same applies to the Hüller record as to the one from Funtensee in the Alps. It exists because there was already a scientific measuring station there at the time and the measured values were already being recorded accurately. Perhaps, and probably even, it was even colder elsewhere in Germany at the time. But no one measured it. Well, bad luck, but never mind, the Hallertau is and remains the record holder.

This year, in 2026, the Institute for Hop Research will celebrate another record: its 100th birthday. The museum’s collection includes numerous items from Hüll, such as equipment, pictures, records, and literature. Among them is the estate of Hüll’s “weatherman” Josef Jehl, who left the museum many weather records. But those are other stories again.