Hop dawn

About the vanished Aischgrund hops region

To the west of Nuremberg continue on the A73, which then becomes the B8, exit at Langenzenn and you’re there. Continue to Neustadt, then turn right via Uehlfeld and Lonnerstadt to Höchstadt. There is no longer any indication that one of the most important hop-growing regions in all of Germany was located here 100 years ago. Aischgrund. A fitting name, at least for the idyllic, flat landscape along the little river Aisch.

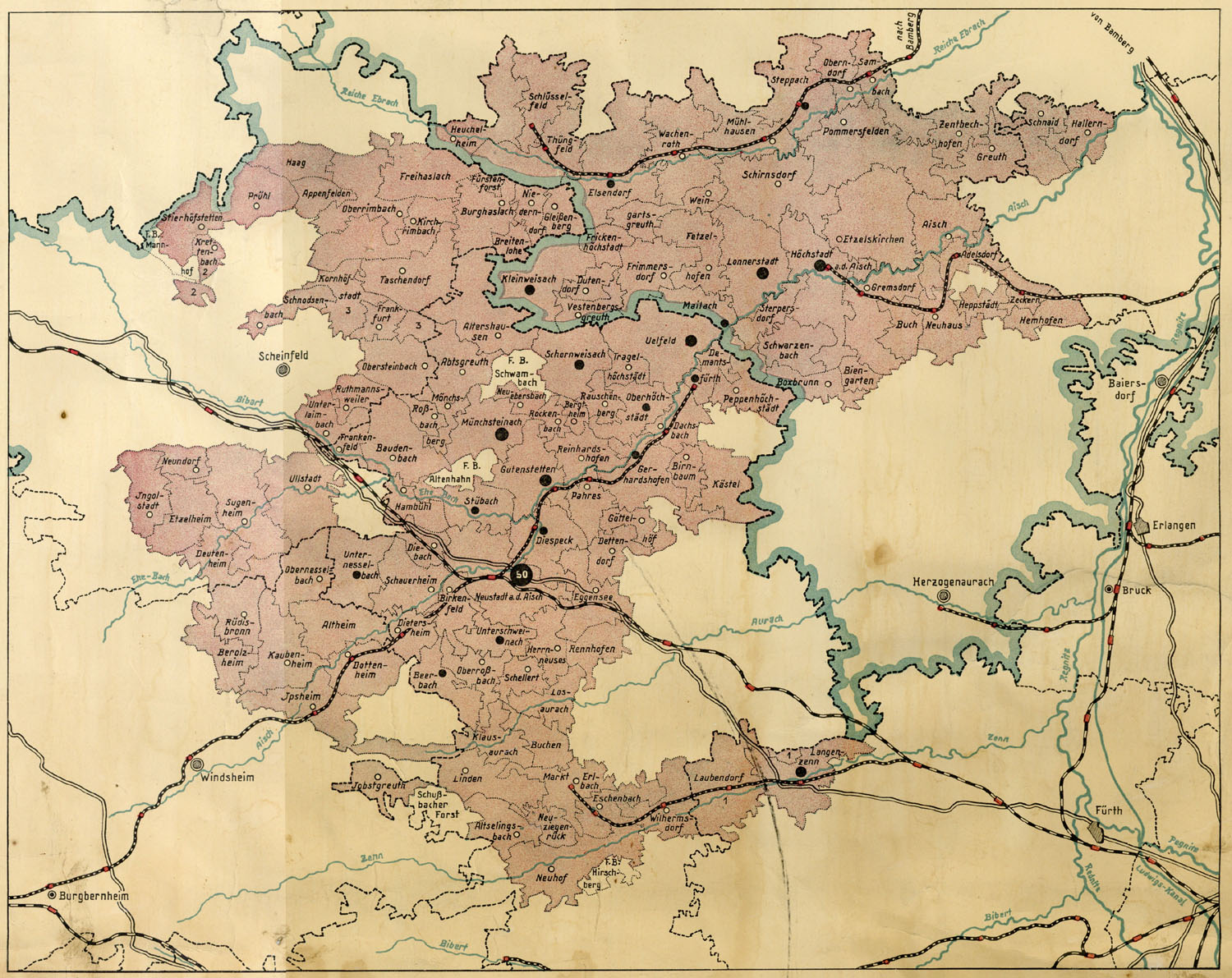

For the hops area, this is no longer quite so obvious. Because when the boundaries of the Aischgrund hop growing area were defined at the end of the 1920s, large parts of the river region in the north-east and especially in the south and west were not wanted to be included. On the other hand, the Aischgrund suddenly stretched far into the former regions of Bamberg in the north and included places like Markt Erlbach or Langenzenn in the south, which actually had nothing to do geographically with the Aisch.

As everywhere in Bavaria, this determination was made in 1928 as part of the “Hops Origins Act”. Only from this point in time was it legally regulated whether and under which regional seal a hop farmer had to market his goods: Hallertau hops, Spalt hops, Aischgrund hops. Pure state-controlled branding policy. Anyone who wanted to grow hops but lived outside the borders of a growing area could only try to supply a local small brewery directly. Big international business was over. It is therefore clear that in the run-up to the drafting of the law, all possible places tried to be part of it. It doesn’t matter whether you didn’t really fit in geographically, as in the case of Langenzenn, or whether you came from a completely different political past, like Schlüsselfeld in the Würzburg area.

Map of the hop growing region Aischgrund, 1930

As everywhere in Germany, there have been hops in the Aischgrund since the Middle Ages. If you wanted to brew beer, you needed hops, and people were reluctant to get them from far away. At that time there was no mention of cultivation areas.

After the Thiry Year´s War, the respective sovereigns then tried to make the cultivation of hops interesting for their subjects. In the Aischgrund there were the prince bishops of Bamberg on the one hand and the margraves of Bayreuth and Ansbach on the other. Anyone who opted for hops received lower taxes, cheap hops poles, a certificate or even cash prizes.

Even more than such aristocratic tokens of favor, it was the increasing industrialization and above all the beer boom of the 19th century that really got hop growing going in the Aischgrund. Around 1830 more hops were grown around Neustadt, Höchstadt and Langenzenn than at the same time in the Hallertau, which was also just beginning to grow and develop. When it was decided in 1858 to lift the sulfur ban on hops, first in Middle Franconia and only four years later in the whole of Bavaria, the entire region was finally sucked into the hop gold rush. With that, the last barriers to the international hop trade had fallen. If you look at the map, however, where hops were grown at that time, you could almost speak of a growing area in Middle Franconia that flowed more or less seamlessly into the bavarian Hallertau. Hops grew from Dachau to Bamberg, from Ansbach to Amberg. The centers were called Spalt, Hersbruck, Hallertau and – Aischgrund. As late as 1905, long after the boom was over, Neustadt an der Aisch, with an incredible 380 acres of hops, ranked first among all hop-growing communities, well ahead of Spalt with 270 and Wolnzach with 262 acres. If you like, the center of German hop cultivation lay here.

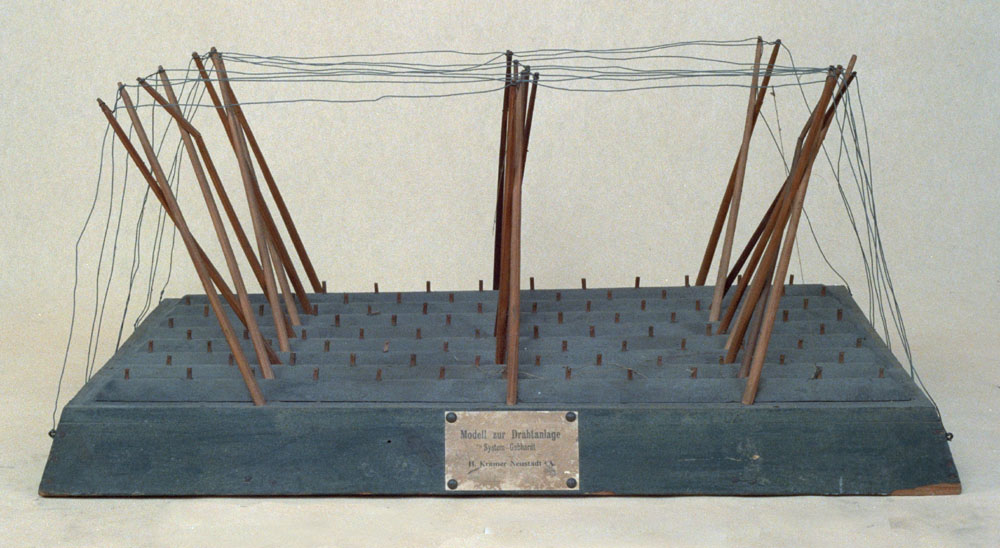

Inevitably, a culture of its own developed. There was a separate Aischgrund hop variety, the Aischgrund Late Hops. A resourceful designer named Johann Gebhard from Neustadt developed a special Aischgrund hop wire trellis that spread everywhere. The roofs of the Aischgrund houses and barns were given “hop dormers”, a kind of ventilation roof hatch so that the many hops could dry better.

Modell einer Aischgründer Gerüstanlage, um 1930

Perhaps the most important joker in the fight for market shares was the close connection between the region and the hop trade. Outside of Franconian cities such as Nuremberg, Würzburg or Neustadt, from which they had been expelled in the late Middle Ages, many Jewish families had settled in the rural communities of the Aischgrund, tolerated by the respective sovereigns, for whose favor they naturally received a substantial fee had to pay. When hop growing got going towards the end of the 18th century, many Jewish traders took advantage of the opportunity. Initially on foot with a basket on their backs, but soon as an established trading company, they bought the well-known Aischgrund hops from the farmers and delivered them to the brewers all over Germany, later to the whole world. When more and more Jewish families moved to the nearby towns from the middle of the 19th century, Bamberg and above all Nuremberg developed into the most important trading centers for hop growing in the whole world. Right in between lay the Aischgrund. Many of the former small traders turned into real global players in the international hop trade.

Examples abound. A man like Gustav Buxbaum, born in Vestenbergsgreuth in 1839, not only established a large hop trading company in Bamberg. As a co-founder of Epple & Buxbaum, he later created one of the most important agricultural machinery companies in the entire German Empire. Joseph Kohn, son of the hop dealer Mayer Kohn from Markt Erlbach, was the first Jewish citizen who was allowed to settle in Nuremberg again in 1850. Bankhaus Kohn later developed into the largest private bank in Bavaria. Marx Tuchmann, hop trader from Uehlfeld, derived his German name from his part-time job in the hop cloth trade. His son Philipp later ran a flourishing hop trading business in Nuremberg and later even in Dessau. Some, like the merchant families Uhlfelder or Erlbacher, immortalized their origin right away in their surnames. The series could be continued indefinitely.

Ultimately, however, the success seems to have been fatal for the Aischgrund hop farmers. In 1889, as many hops were produced in Germany as only 100 years later. Inevitably, hop prices collapsed massively. As a way out of the crisis, the state authorities proclaimed quality hop cultivation. Modern cultivation technology, uniform varieties, plant protection, clean designation of origin, all of this was now very popular. Among other things, hop farmers of the Aischgrund sought their salvation by observing things from their now more successful competitors in the Hallertau. Processing plants based on the Hallertau model, trellis systems from the Hallertau and, above all, the Hallertau hops themselves. At the end of the 1920s, 5/6 of the Aischgrund hops consisted of the Hallertau Mittelfrüh variety that had been procured there.

But the end couldn’t be stopped. After the collapse in World War I, hop cultivation in the Aischgrund could no longer get off the ground. The farmers lacked the size of the farms and the necessary capital for consistent modernization. The influence of the Bamberg and Nuremberg traders had declined massively. Aischgrund hops fell into disrepute more and more. Cultivated areas and yields collapsed.

The beginning of National Socialist rule then finally heralded the decline. In the jagged-militaristic tone of the new rulers, the Aischgrund hop-growing region now waged “a hard and difficult fight for its right to live” and the Aischgrund was stylized as the “sick man (…) of all German hop-growing”. When the wartime economy was in full swing in 1942, permission to grow hops was simply withdrawn from the Aischgrund. After the war, a few farmers returned to hops, but the Aischgrund could no longer manage more than one cultivation for local small brewers. At some point even the last small farmer gave up without a murmur.

Neustadt an der Aisch, 1865 (Photo: Dr. Wolfgang Mück, Neustadt a.d. Aisch)

Nevertheless, it is amazing how radically hops have disappeared from the landscape. Every now and then you come across hop vines that have been released into the wild along streams or at the edges of forests. If you drive through the villages with alert eyes, you will discover a hop dormer on one or the other farmhouse. But there is not much more to be found. No local museum, no matter how small, has taken on the subject, no collection of old equipment anywhere, at most a few old photos are stored in the local archives, in the local chronicles here and there an old picture of a town view, on which a few hop sticks are also shown. The only hop building in the entire region that has been placed under monument protection leads a sad existence as a littered, windowless skeleton, which you can see from every corner that its new owners can hardly wait until it finally collapses.

The traces of the Jewish hop traders have almost completely disappeared. For a number of years, dedicated local researchers have been studying the history of the Jewish communities in the Aischgrund, but hops inevitably only play a minor role. In the remaining Jewish cemeteries there are still one or two tombstones whose engraved surname can be linked to a family of hop dealers.

Many a magnificent old house still bears witness to the former splendor of the Aischgrund hops, above all, of course, in Neustadt an der Aisch. Without the former success of hops, it would probably never have been built. In the course of time, however, the knowledge about it will also have faded.

Title: Old hop barn with dormers in Gutenstetten.