The Wolnzach “Hop Vine Processing Company”

During the war, attempts were made to process hop vines into textile fibers.

(Special thanks to Rudi Pfab, Wolnzach, who provided most of the sources for this article).

The idea was actually quite old. Supposedly, the ancient Babylonians had already experimented with this in “time immemorial” – which is rather unlikely, since hops did not grow there at all, due to the length of the days. But in 1754, a certain Pehr Schißler reported in detail to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences how he had begun processing hop vines into textile fibers on his estates in central Sweden, similar to hemp. Hop fabric was said to be particularly robust and was therefore popular for sackcloth, rope, and carpets. It was considered warming, in contrast to cool cotton. However, it was difficult to bleach, which limited its use in clothing. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there were repeated reports of such activities in Bavaria, Württemberg, and Thuringia, as well as in England, Bohemia, and Russia.

As is well known, hops are only cultivated for their hop cones. The huge quantities of vines and leaves were always considered waste and were used at best as bedding for livestock or returned to the hop garden as green manure. It is actually surprising that further processing into textiles or yarn never really took off. A short report in the Allgemeine Brauer- und Hopfenzeitung from 1887 provided a clue as to why this might have been the case: “Unfortunately, however, attempts in this direction have so far been hampered by a lack of cooperation on the part of producers,” sighed the author. In other words, hop farmers were, to put it mildly, only marginally interested in processing the vines. This was probably also due to the fact that the entire transport and preparation effort was not profitable for them, i.e., the vine processors did not pay them decently.

Hop vine processing in Wolnzach, 1941.

On September 17, 1918, Prof. Dr. Udo Dammer, director of the Botanical Garden in Berlin, wrote a circular letter to all botanical institutes in Germany. He urgently recommended that a Germany-wide directory of wild hop locations be created. Due to the war, hop cultivation had declined massively. However, he had developed a working process for hops, “breaking down the fibers so that they can be spun into fine yarn.” Urgent action was needed, because hops were one of the plants “that should enable us to persevere.” Because: “Before the war, we imported 470 million kilograms of cotton, which we now lack, so that 97% of all German cotton spinning mills are now at a standstill.” In other words, in his opinion, the production of hop fibers was a war-related necessity in order to avoid defeat in the four-year-long slaughter of nations.

As we know, the First World War was over just two months later, so Dammers’ initiative came to nothing. Little happened in the years that followed. Until September 1934, when Hugo Hampp, Bavarian state inspector for hop cultivation and managing director of hop research, wrote a short report. The topic: “The use of hop vines for fiber production.” Hampp looked at the problem from a practical perspective and at the same time from a research point of view: after the hop harvest, the many ingredients in the vine – proteins, sugars, minerals – had to be able to flow back into the stock. The vines should therefore not be cut too early. However, it first had to be clarified whether the vine was still suitable for the production of textile fibers.

The mood was not necessarily bad: female workers processing vines in Wolnzach, around 1942.

Hampp’s remarks were particularly controversial because he began with the sentence: “It is clear that we must do everything we can to meet the demand for fiber raw materials in our own country.” Why? Two years later, it became clear what he meant. On October 18, 1936, Adolf Hitler personally issued a “Decree for the Implementation of the Four-Year Plan” and entrusted its implementation to none other than one of his closest confidants, Hermann Göring. In short, the aim of this plan was to make Germany independent of foreign supplies within four years so that it would be economically capable of waging war. In the case of textiles, this meant above all independence from cotton supplies from overseas territories. Hops were to make an important contribution to this.

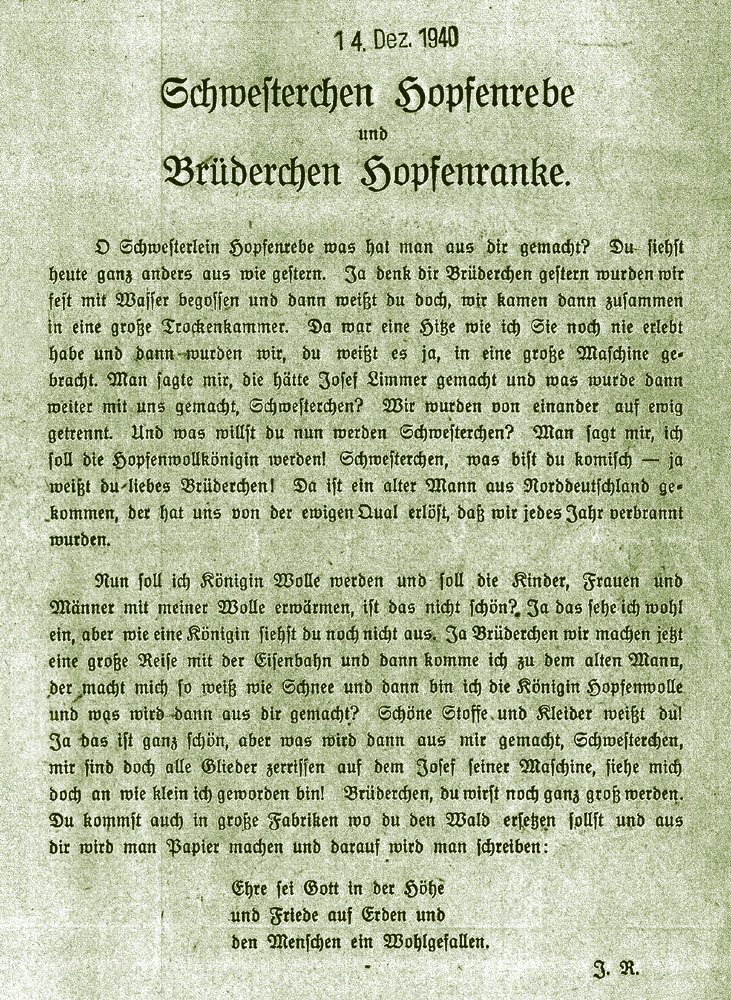

Brother and sister – in hop country. This fairy tale was recited at the inauguration in 1940.

An Upper Franconian entrepreneur named Georg Lattemann then succeeded in developing a promising technique. He founded a “Hopfenrebenaufschließungsgesellschaft K.G.” (Hop Vine Processing Company) based in Bremen and approached the market town of Wolnzach about setting up a processing plant. The location of the planned “Hopfenstracklfabrik” (hop processing plant), as the Wolnzach residents later christened it, was not chosen entirely by chance: on the one hand, it was directly adjacent to the Wolnzach railway station, which made it easy to transport the finished textile bales. On the other hand, it was right next to the Wolnzach, the small river that flows through the hop-growing town. This was because water was needed for the necessary soaking of the vines, known as “roasting,” in order to break down the fibers more easily. This process had long been known from flax processing. Construction began in 1939. Until the factory was completed, several rooms were made available in the Wolnzach processing hall (preparation facility), where fiber extraction began. Meanwhile, war had broken out again.

The “roasting,” or soaking of the vines, was particularly important in order to break down the fibers.

Prominent figures at the site. One of the gentlemen is probably inventor Georg Lattemann. In the middle is Adolf Rebl, head of the planters’ association.

This meant that farmers no longer had many options for refusing to participate. After all, hop processing had been classified as essential to the war effort. “By delivering their hop vines, the Hallertau hop farmers are proving that they are willing to do their part when it comes to helping rebuild the German economy.” Said Adolf Rebl, managing director of the Hallertau and Jura hop growers’ associations, in 1940. In the fall, the delivered vines were stored in huge piles on the outskirts of Wolnzach. Before delivery, the wires had to be pulled out of the vines. More than 50 women and girls were busy removing the remaining leaves, stacking them into manageable quantities, sprinkling the piles with water, and removing the woody parts in large threshing carts. The remaining parts of the vines were also to be reused: wood waste in the paper industry, mucilage as an emulsion for imitation leather or imitation cardboard. The first wagon with hop wool and hop wood left Wolnzach station shortly before Christmas 1940.

Hop vine delivery 1: A huge load. It was no longer possible to ride along on the driver’s seat.

Hop vine delivery 2: The Schlüter tractor made things a little more comfortable.

However, it is no longer clear what actually happened in and around the Strackl factory in the years that followed. In any case, there seem to have been divided opinions about the obligation to deliver the hop vines. Lattemann, Hampp, and Rebl were of the opinion that such an obligation existed. Apparently, quite a few hop farmers, especially those in other growing areas such as Spalt or Hersbruck, or even in the Saazer Land, which now belonged to the Greater German Reich, saw things differently. The supply of the factory seems to have never been properly organized. The increasingly grim war situation may have contributed to this.

In any case, a later reporter said that the factory never really got off the ground. Manufacturer Lattemann disappeared without a trace at some point, and in 1945 the Wehrmacht summarily confiscated the building as a supply depot. At the end of the war, the warehouse was looted, leaving the hall as an empty rubbish dump. The large piles of vines next to the factory had long since gone up in flames. This was done out of fear of the dreaded hop pest, the hop sawfly.

Construction site of the hop vine factory. Safety on the construction site no longer fully complies with today’s regulations.

After the war, the Wolnzach hop merchant Josef Trapp bought the hall and turned it into a hop processing plant. Later, it was taken over by Lorenz Thoma, a haulage contractor from Wolnzach and one of the most important hop transporters in the Hallertau region.

The idea of processing hop vines into textile fibers never got beyond the theoretical stage.