The rebel from Pötzmes

When hop farmers and state-imposed plant protection clashed

When thing become difficult enough, even the most democratic community cannot and will not tolerate too much freedom of expression. Events in hop growing in the 1920s are strikingly reminiscent of conditions during the Covid-19 pandemic. When things have to happen quickly, science no longer has time to take everyone with it. And its claim to truth inevitably reaps a lot of mistrust. And, of course, contradiction.

The tracks first appeared in 1924. The weather was lousy that summer. Too wet, too cold. Brown spots appeared on the hops. Farmers and officials believed that the green gold was struggling to cope with the unusual weather. It will get better. But when the “cone tan” appeared again the following year, people became more nervous and began to take a closer look. But by then it was almost high noon. Shortly before the 1926 harvest, almost no healthy hops could be found in the center of the Hallertau. A catastrophe of unimagined proportions was on the horizon. Hallertau hop growing was on the brink of collapse.

Research Institute for Hop Growing in Hüll near Wolnzach, around 1950

Just how serious the situation was can best be seen from the fact that suddenly everyone, really everyone, was pulling in the same direction. Farmers, merchants, brewers, scientists and the state apparatus all showed efficiency. What had initially been glossed over as an unsightly discoloration soon turned out to be a new kind of disease. A name for the hop pandemic was quickly established: Peronospora. Previously only known in viticulture, the fungal infestation had suddenly made itself at home in hops for mysterious reasons. Competitors in the United States were suspected of some kind of machination, however the insidious disease attack on German hops may have taken place. Ultimately, however, it didn’t matter where the hop plague came from. Action had to be taken. Immediately.

And this was done with rare unity. As early as 1926, an association of all those affected bought the Hüll hop estate. Part of it was converted into the Research Institute for Hop Growing, which still exists today. It will soon be celebrating its 100th birthday. The young agricultural councillor Hugo Hampp was appointed as its director. He was later nicknamed the “Savior of the Hallertau”, and not without good reason. Hampp’s most urgent task was to quickly teach the farmers how to combat peronospora. A solution of copper and lime proved to be the No. 1 weapon. Initially mixed independently in large plants, the copper-lime solution was soon also available in ready-made form from the Wacker chemical factory in Munich. The “Bordellais Broth” was, you guessed it, a tried and tested mixture from viticulture, where the growers had already gained experience with fungal infestation.

Stefan Krojer, around 1930

It was certainly no easy task to teach the untrained hop growers how to use chemical agents. However, a completely different challenge was even greater. Better today than tomorrow, they had to invest a lot of money in the purchase of a new spraying machine. Even the very simple version of a hop sprayer, a backpack sprayer, cost around 80 marks. The whole thing was available as a wheeled cart sprayer with a 100-liter brass tank and three wheels, starting at 270 marks. In the end, the only sustainable design with a motor drive and accessories cost a hefty 1,500 marks.

And now, at the latest, there was resistance. And no other figure reflected this spirit of resistance more clearly than that of a man who was eventually publicly declared to be “mentally abnormal”: Stefan Krojer, from the Hallertau village of Pötzmes. An independent spirit that he was, Krojer spread his very own ideas on practical hop growing and sensible crop protection throughout the Hallertau region in both oral and written form from the late 1920s onwards. The official assessment of Stefan Krojer was relatively unambiguous: he was a “charlatan” whose nonsensical ideas “could really only have been formed as a figment of a sick mind”. As I said, that was the official verdict. The opinion of the hop farmers was strikingly different:

“Krojer was a very open-minded person, very eloquent. And he was a good contact person. And you have to say that the man was really able to offer people in the Hallertau region something that was a great help to farmers, especially in hop growing, so that they could work more easily again with the hop sprayers” (Mr. A., hop farmer, born in 1916).

—————————-

“Krojer invented so many different things that people were surprised. (…) He had a scythe, a folding one, and he invented the automatic spraying machine. We were some of the first, I won’t forget that, there was only one man who sprayed hops (…) he invented practical things that were a great relief for the farmer” (Mr. B., hop farmer, born in 1920).

Scythe by Stefan Krojer, for cutting the hop bines in spring, around 1930

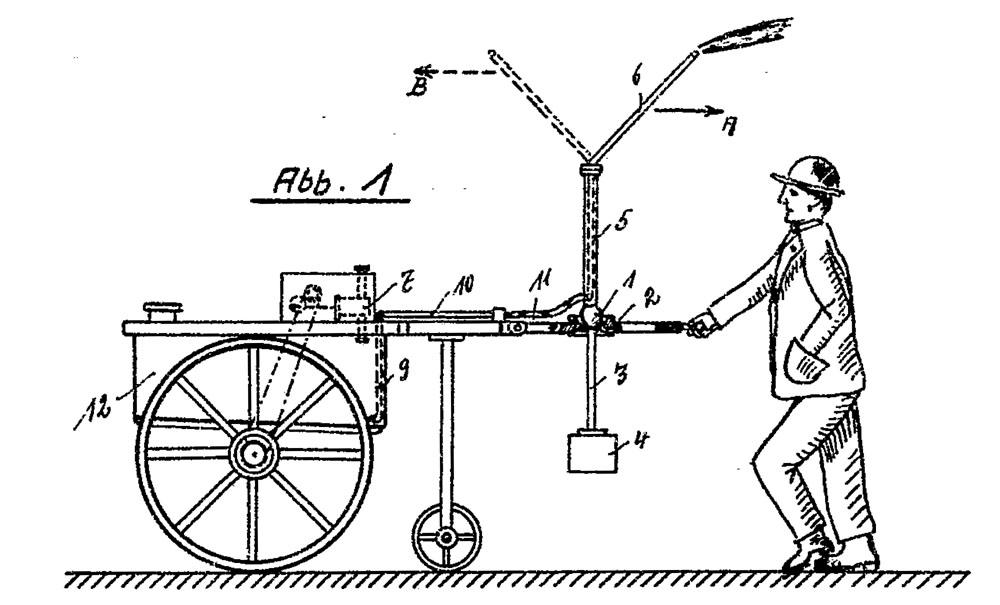

Krojer’s effectiveness stood in marked contrast to the official assessment of his person. His scythe made hop pruning much easier in the spring and became a bestseller. His “pendulum atomizer”, which he even had patented, also found numerous buyers. Accordingly, most of his meetings were “full to bursting”, as newspapers wrote in 1931. What he certainly did not lack was self-confidence: “It is indisputable that the riddle of peronospora has been solved, for which the entire German hop-growing community owes me a debt of gratitude.”

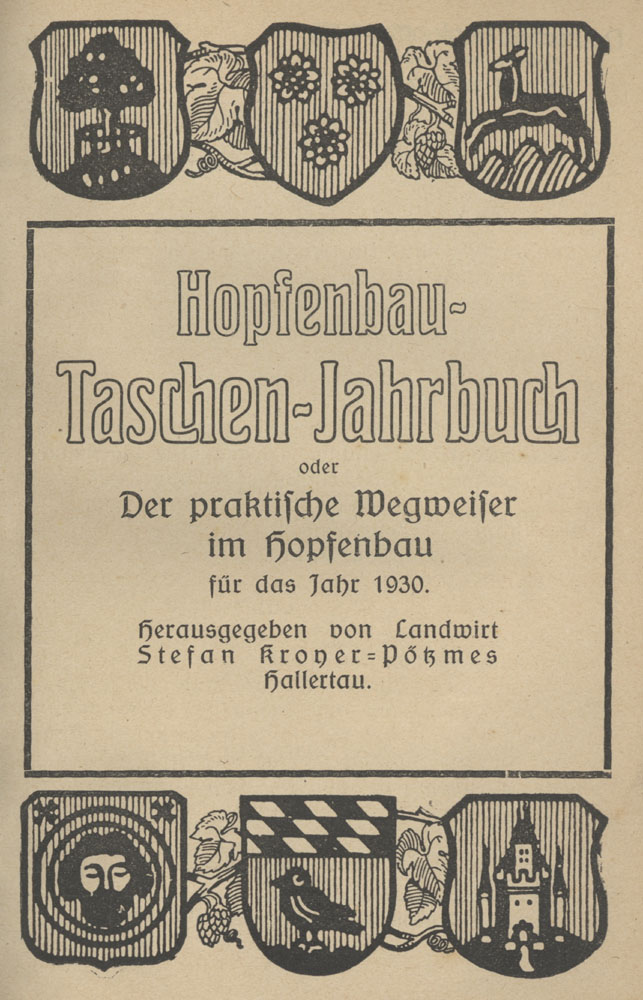

Sometimes, however, Krojer’s activities seemed like a caricature of the official propaganda campaign. He distributed his spraying agents in wine and lemonade bottles, as an aid to persuasion he presented a self-produced film with the unconventional title “Alpenglow” and his self-published “Hop Growing Pocket Yearbook” presented a whole collection of somewhat more “special” advice, constructions and equipment for hop growing. He concluded his guide with the words: “Only a reduction in production costs, green color and quality cultivation can save the hop-growing farmer!” In the end, he even founded his own “experimental station for hops and fruit growing” in his home town. His opponents were stunned: “Krojer emphasized in his lecture (…) that spraying the plants 4 days before the rain was particularly important. However, science is no longer able to keep up with this.”

Clearly, two worlds collided here. And it soon became clear that it wasn’t just a question of true or false. Like an upright Don Quixote of hop growing, he rode his attacks against the windmills of officially decreed modernization. In the rhetoric of the “Mussolini of the Hallertau”, as Krojer was later known, a peasant stubbornness appeared that did not want to be told what to think and do by the state authorities. “Take interest in my person, then you will see better into the darkness of the night in German hop-growing”, Krojer urged his opponents.

Pendulum atomizer by Stefan Krojer for plant protection in hops, extract from the patent specification from 1928

Krojer’s more objective arguments showed that it was by no means just “stupidity or malice” at work, as his opponents claimed. He not only accused the president of the German Hop Growers’ Association, Franz Edler von Koch, of ignoring the “urge and the great need“ of German hop growers: “As a large hop grower, you primarily have the advantage of saving 2/3 of the work”, he accused von Koch, at the time the largest hop grower in the Hallertau. When Krojer finally claimed that the state functionaries had deliberately argued in favor of backpack and cart sprayers at first and then soon after for motorized sprayers and that they were “robbing the farmers of their money”, he completely transformed himself into the mouthpiece of the many insecure small hop farmers. He appealed to their solidarity: “Hop farmers who still want to maintain their livelihood must appear. It is possible to save them, but they have to want to. Show up en masse, only then is success possible.” Consequently, he soon made clear political demands: Lower the price of electricity and beer, reduce social burdens, standardize the fight against peronospora, grant compensation for the losses caused by the costly measures.

When he was forcibly removed from an opposing meeting in the early summer of 1931, all the verbal dams finally broke: “That was the signal to strike out”, he rumbled, “now the sin registers are all being pulled out, and what cannot be bent must be broken, everything is being thrown overboard, and all those working in the hop growers’ association have to bear the consequences. Science has been turned upside down and has to put up with it. Those are my last words.”

Hop-growing Pocket Yearbook by Stefan Krojer, 1930

They were indeed, but not what he meant. Krojer himself became a victim of the crisis situation that he tried so hard to avert. The high costs of his campaign swallowed up considerable parts of his fortune. His radical stubbornness stifled any willingness on the part of the authorities to support him. Finally, several lawsuits for libel and defamation silenced him for good: Krojer was banned from speaking at the beginning of the 1930s.

The official authorities had prevailed. Numerous hop farms that were unwilling or unable to accept the new era of plant protection had to stop. Anyone looking for solutions to pressing hop-growing problems now had to rely on chemistry and science.

Stefan Krojer died in 1966 and is buried in his home village of Pötzmes.