The Walk-in Hop Cone

Museum items – for 20 years (3)

By Christoph Pinzl

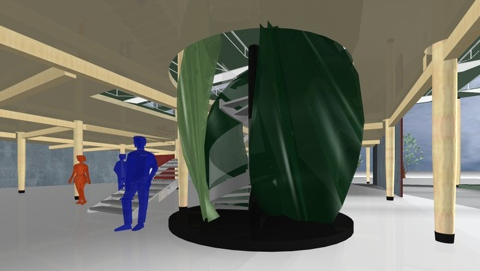

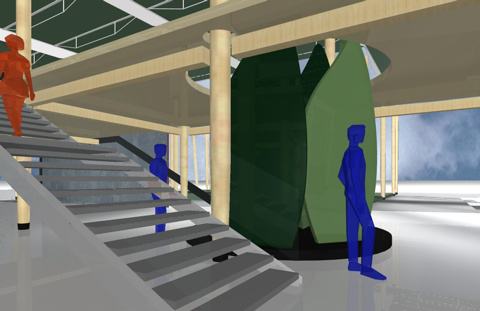

It was one of the very first ideas we had for our future museum. A giant hop cone that visitors could walk into – that would be awesome. As an introduction to the permanent exhibition, the museum tour. Right at the beginning of the story, the journey through time, where hops simply exist and – historically speaking – no one was interested in them yet. Because people hadn’t discovered them yet, because there were no people yet who could discover them. Just nature and, in the middle of it all, hops. A larger-than-life model that makes a big impression right from the start, definitely something for all the senses. Eyes, ears, hands, nose – everything should be stimulated. Not unlike a US science center, where combining spectacle and knowledge transfer has always been the norm.

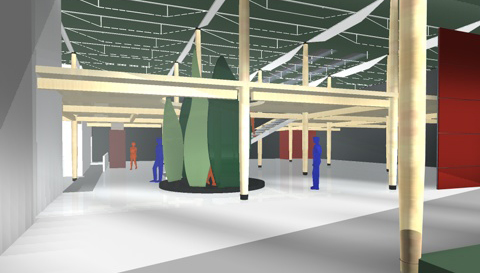

The Walk-in Hop Cone from the inside.

The giant cone is therefore also meant to have a symbolic effect. Because, as we know, hops appeal to all the senses. A good hop evaluater can not only smell whether the hops are any good, he can also tell by the right color, he can recognize the right moisture content by the right rustling sound, and he can feel whether the quality is right. This is roughly how our visitors should be put in the right mood. With scent stations, sound collages, spectacular lighting effects, that sort of thing. Inside, a kind of cave atmosphere, where golden lupulin balls glisten behind the large cone leaves, keyword (hop) gold rush.

In addition, the sheer size of the cone should symbolize what hops meant to the regions and their inhabitants who devoted themselves to it: an immense amount. Going one step further, the cone was also intended to address and symbolize the peculiar relationship between large and small in hops: the giant plant that grows faster than almost any other, yet from which all you need is a little yellow lupulin powder; the large, diverse world of beer, which is supplied by a single, relatively small hop-growing region; the large mug of beer, which without a single gram of hops would be nothing more than bland sugar water. Admittedly, these are thoughts that do not immediately come to mind when looking at the cone for the first time, but they are part of the basic idea behind it.

To put it simply, we wanted to use the walk-in hop cone as an eye-catcher; after all, you need something that people want to include in their souvenir photos. We certainly succeeded in that. No association gathering visiting the museum, no politician visiting with their entourage, hardly any group tour of the museum that doesn’t line up for a group photo in front of the large hop cone afterwards.

So far, so imaginative. Now all we needed was someone to actually put the whole thing in the museum. Initial inquiries with established set designers were somewhat sobering. According to the creative companies, it was fundamentally feasible, but the price was roughly in the financial range we had estimated for the entire museum interior. So it couldn’t work for the time being.

The main problem was that we wanted something that had to work both from the outside and the inside. Building a large, enclosed sculpture that looked like a hop cone was feasible, regardless of the material. Creating a room that, when you entered it, looked like the inside of a cone was also feasible. But doing both at the same time, and with all the not-so-trivial requirements of fire safety, accessibility, safety for visitors and exhibits, and technical equipment, was difficult. Anyone who entered a stage set knew where they couldn’t lean and didn’t mind if the wooden slats were visible behind the magnificent facade, but for museum visitors, the illusion had to be complete. And on top of that: an cone from the inside, what was that supposed to be? Hop cones are not hollow, so how could anyone move around in something like that? Besides, a hop cone tapers at one end and has a stem at the other, so would the walk-in specimen float above the ground, so to speak? And anyway, where was the boundary between naturalness and abstraction?

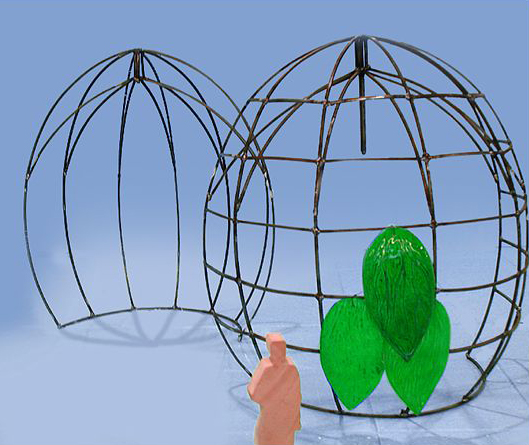

The fact that the walk-in cone could actually be admired at the museum’s opening in 2005 was certainly one of the few positive side effects of the museum’s extremely long planning period, which, as is well known, took 21 years. Over the years, there were repeated attempts to realize the cone, plans were changed, and various artists, companies, and creative people sought a solution. The man who finally got to the heart of the matter named Politor, Günther Politor. His company, Werk 7, not only brought a wealth of experience in building all kinds of sets, whether for theater, film, or museums, but also offered the whole project at a price that was within our limited budget. We are still grateful to him and Werk 7 today.

Roughly speaking, Mister Politor first designed a metal frame for the walk-in cone, not unlike an egg-shaped igloo or yurt. He then layered the cone leaves on top, with a separate layer for the outside and the inside. Inside, each leaf was then cut to create the aforementioned hollow space. The spindle of the cone, to which the golden lupulin grains are attached in a spiral pattern, was displayed prominently from above. Each leaf was individually handcrafted from a material not unlike a sleeping pad. Naturally, it complied with fire safety requirements. More than just a backdrop. A work of art, without a doubt.

The sensory stations inside, the listening station, the smelling station, and the illuminated panels were then developed by our museum designers in collaboration with the museum management. Even though some of the technical elements have since been updated, our walk-in cone still looks amazingly good even after 20 years. Certain fears that the cone leaves would eventually succumb to the many curious hands of visitors have not been confirmed. As in real life, the hops hold their own despite all adverse external influences.