His Majesty Hindenburg and the hops

How a family of small farmers asked the President for help

By Christoph Pinzl

The year 1928 had actually started quite well. For the first time in a long time, things were looking up again for the hard-hit hop farmers. The World War had been over for ten years, as had the period of hyperinflation of 1923 with its absurd billions and trillions. The hop industry had also got the recent scourge of the new fungal disease down for the time being. Even if it took a lot of effort, not least financially. But this year everything seemed to be going well. Even the weather had cooperated. Finally, the harvest was excellent, the vines were heavily laden with cones in the hop gardens. Germany’s brewers were already impatiently awaiting the hop raw material. People were drinking beer again, business was going well. And as it looked, even this bumper crop of hops was not enough to meet the planned beer output. Some brewing barons had already signaled top prices. They wanted to pay 300 Reichsmarks this year in any case, for every hundredweight of hops. So what more could you want?

But somehow everything went off the rails again. At the beginning of September, the situation on the hop market still looked very good. But at the end of the month, sales suddenly collapsed. Not all hop traders were willing to accept the prices dictated by the growers. When they approached the Wolnzach and Mainburg hop farmers and the farmers only casually and a little snobbishly raised three fingers (for 300 marks), the traders left annoyed. And they went elsewhere to buy. Because there had been good harvests elsewhere too, not least abroad. As a result, prices remained at rock bottom and the Hallertau farmers were ultimately forced to sell their hops well below market value and often even below production costs.

The mood was not particularly good in the harvest year of 1928, here at the farm of Nikolaus Hausl in Walkersbach (between Pfaffenhofen and Wolnzach).

“Bad mood” was a bit too weak to adequately express the mood among the hop farmers: ‘A terrible agitation and terrorist mood has already taken hold among the hop farmers,’ the German Hop Growers’ Association reported with concern to the Reich government. And attached a whole catalog of measures to the letter, with which the government was to help the farmers out of the mess.

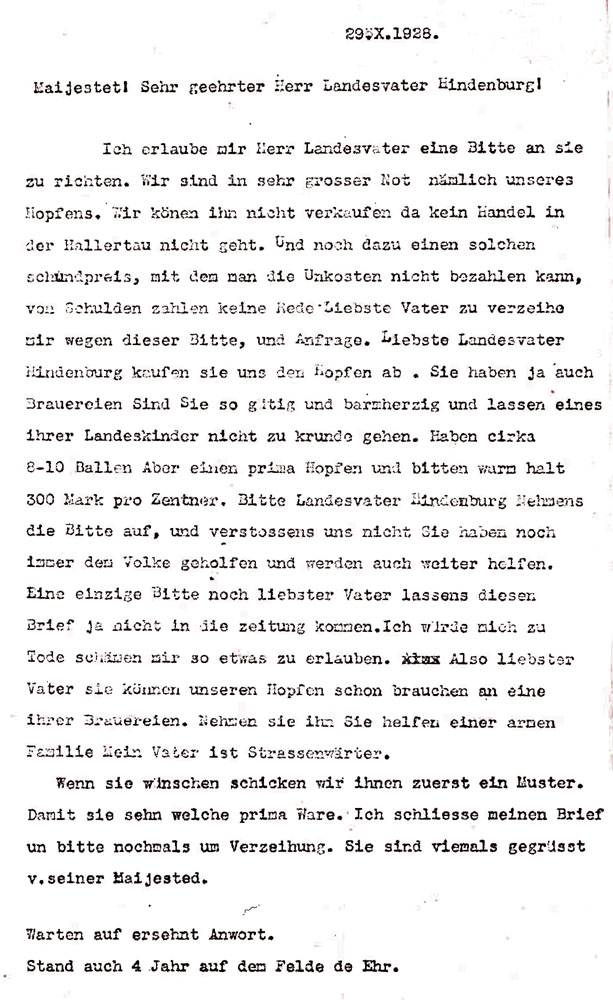

For a small Hallertau farming couple, however, things were not moving fast enough. Perhaps they had seen too many saccharine illustrations in weekly magazines such as “Gartenlaube” or “Illustrierte Welt” about the kindness of kings and queens or similar. In any case, they took matters into their own hands and wrote a letter without further ado. To Berlin, to his “May Majesty”, Mr. “Father of the Nation Hindenburg”. They were “in great need” because “no trade in the Hallertau is possible”. And if it is, then at “such a rubbish price that you can’t even pay your expenses, let alone talk about debt”. To cut a long story short: “Dearest Father of the Nation Hindenburg, please buy our hops. You also have breweries. Be kind and merciful and don’t let one of your country’s children perish.” There were still 8-10 bales left “and we would ask for 300 marks per hundredweight.” There they were again, the 300 marks, this time they saved themselves three fingers. The plea became more and more urgent: “Don’t reject us, you have always helped your people.” And because he knew his customers, he added the assurance: “If you wish, we will send you a sample first. So that you can see what great goods they are.” Finally, one more: “Many greetings from His Majesty,” by which the hop farmer certainly did not mean himself.

A copy of the letter to the President of the Reich, Paul von Hindenburg, dated October 29, 1928, made by a bailiff. Some parts have been retouched to make it anonymous.

You have to read the letter a few times and you still can’t quite figure it out. In any case, Paul von Hindenburg was no royal “majesty”, but rather President of the German Reich from 1925. As the “hero” of the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia, he had taken over the “Supreme Army Command” together with Erich Ludendorff during the First World War and was thus not entirely innocent of the death of millions of people and the collapse of the Reich. He was also instrumental in one of the most unfortunate conspiracy theories in history, the so-called “stab-in-the-back legend”, according to which the defeat in the war would have come about only through socialist and democratic machinations in the Reich. Not least because of this, Hindenburg had managed to present himself to the public as a kind of shining light, who, despite his role in the war, was offered the presidency of the Reich again a few years later. The idea that he, of all people, was supposed to have “always helped the people” is based on a very idiosyncratic logic. And as a brewer, he had not exactly made a favorable impression so far. Whether Hindenburg ever actually laid eyes on the letter is not known, but it is doubtful. And if he had, he would hardly have painted a picture of a magnanimous “father of his country” with a full beard and a benevolent smile, promising help to the poor farmers from faraway Bavaria.

Russian prisoners of war during the First World War, 1916, on a farm in Eschelbach near Wolnzach.

With all his spelling and phrasing mistakes, with his daring mixture of subservience and wheeling and dealing, one is tempted to dismiss the letter as a joke and make fun of it. But the desperation was real and anything but a joke. And the hop farmer who wrote the letter also made a very cool and not so fairytale calculation when he added “stood for 4 years in the field of honor” after his greeting to Hindenburg. Not the hop field, but the battlefield of the First World War.

Fresco painting “Heimkehr” (homecoming) in the vestibule of the war memorial chapel in Eschelbach near Wolnzach, inaugurated in 1922.

So 1928 was a bad year, but the following year, 1929, was even worse. The world economic crisis and disastrous overproduction caused the hop market to finally collapse. With it, countless hop farmers’ livelihoods were lost under an insurmountable debt burden. 70% of the small and medium-sized hop farms were no longer able to pay their dues. In the following years, a total of 186 estates in the Hallertau region alone were sold at auction. Along with them, around 3,800 hectares – no less than 18% – of the total agricultural area was sold at auction.

Until 1933, when a man named Adolf Hitler came to power and led the farmers to believe that everything would now be better. Incidentally, a certain Paul von Hindenburg proved himself to be a useful tool in the office of Reich Chancellor.

Small hop farmers were hit particularly hard by the poor market situation that began in the late 1920s. Many farms were sold at auction.