Nunnery and Deaf Hops

Why men have a bad hand in the hop yard

The former Weihenstephan Professor Lintner is said to have made a comparison that is often used by hop experts: “A hop plantation must be like a nunnery, no man is allowed in there. When man cultivates plants, he does not only try to bring the growth into a suitable form by means of machines and chemistry. He even interferes in the sexual life of the plants. Only female hops provide what all the effort of hop cultivation is for in the first place: Lupulin, valuable raw material for the brewing industry. Male hops are not only superfluous in hop cultivation. It is even seen as a pest to be controlled like aphids and red spider mites. The “Ordinance on the Control of Wild Hops”, which is still in force, has been in force since 1956. It stipulates that any hops growing wild in communities where hops are grown must be grubbed up without restriction.

So anyone who talks about hop cultivation means only female hops. At least nowadays and in Germany. But this was not always the case.

Botanical beginnings

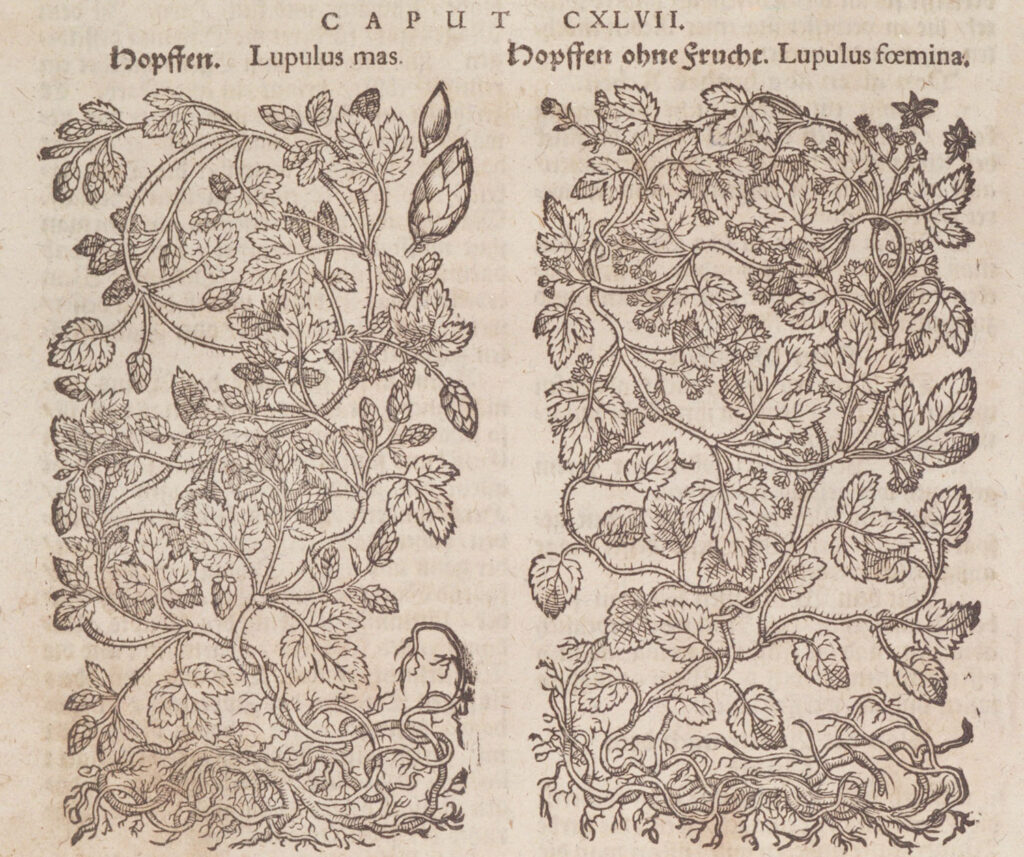

In the thick-bodied herbal books of the 16th and 17th centuries, highly learned reference works on all matters of botany and medicine in their day, the genders were quite readily reversed. Here, the male hop bears umbels, the female the panicles. The Saxon school rector and “hop expert”, Johann Anton Fritsch, had a nice, but also rather twisted explanation ready. In the herbal books, the designations “foem.” and “mas.” for female and male had been confused. Male hops are those without yield, the “deaf” hops, which in Latin means “foemina”, ergo it is the “Lupulus foem”. Why, however, the female then of all things should be called “mas.” should be called, teacher Fritsch remained guilty in his explanation.

The male hop is the deaf and therefore “foemina”. Clear.

Others, such as the Altdorf scholar Johann Ehinger in his Latin doctoral thesis “De Lupulo” of 1718, omitted the difference altogether. There was no such thing as male and female hops. Or rather, each plant had both sexes in it and it depended on various factors which one came to the fore. The hops seemed to fertilize themselves, so to speak.

Gender confusion to and fro, in any case, it was always clear that one wanted to grow only the hops that bore the lupulin-containing cones. The other sex was of no interest.

Pro and contra

This changed at the beginning of the 19th century. The methods became more scientific, the means more sophisticated. Hop cultivation increased throughout Germany, as did the prices paid. Gradually, everyone was able to tell the difference between male and female. So far there was agreement. But now disputes began about how to handle male hops properly and professionally. Some, like the brewer Leopold Limmer in Staffelstein, did not care at first. Male hops were not necessary to obtain cones. Whether or not they were tolerated in the hop yard was a matter for each hop grower to decide for himself.

But there were also more critical voices. Franz Olbricht, a Bohemian hop grower and book author, recognized as early as 1835 that the lupulin in fertilized cones was coarser than that in unfertilized ones. Moreover, knowledgeable hop growers noticed that too much masculinity in the hop yard left too little room for the cone hops to develop and wasted nutrients and light unnecessarily.

A man and his preservatives: so that no misfortune happens in the trial hop garden, the male hop plants are packed (photo taken around 1950).

But suddenly the mood turned. It was impossible not to notice that fertilized cones were clearly yielding more than the unfertilized ones. And not only because the seeds in the cones increased the weight. Fertilized cones became much larger, the cane bore more and more luxuriantly. In some places it was believed that fertilization even had a particularly favorable effect on lupulin. German hop growers who had emigrated to Australia had the idea of increasing the “quality” of their hops, which were suffering from a “lupulin deficiency”, by importing male plants. It was recommended that for every certain number of female bines, a male bine should be planted in the hop yard, if possible downwind, so that all the cones would be fertilized.

As was so often the case in agricultural matters at the time, the British Isles served as a shining example. Their hop growers had been using this technique for a long time and it was to survive there until the 1980s. Even today, one can still find individual male plants in English hop gardens ¬- to the extent that they still exist. As a result, the hops not only produced higher yields, they also proved to be more stable against pest infestation. English brewers did not seem to mind any loss of brewing quality. In 1908, Ernest Stanley Salmon and Artur Amos, two of the most important minds in British hop research, even tried to prove with scientific precision that the English hop varieties absolutely needed fertilization, otherwise their cones would not grow to their full potential.

Combat message

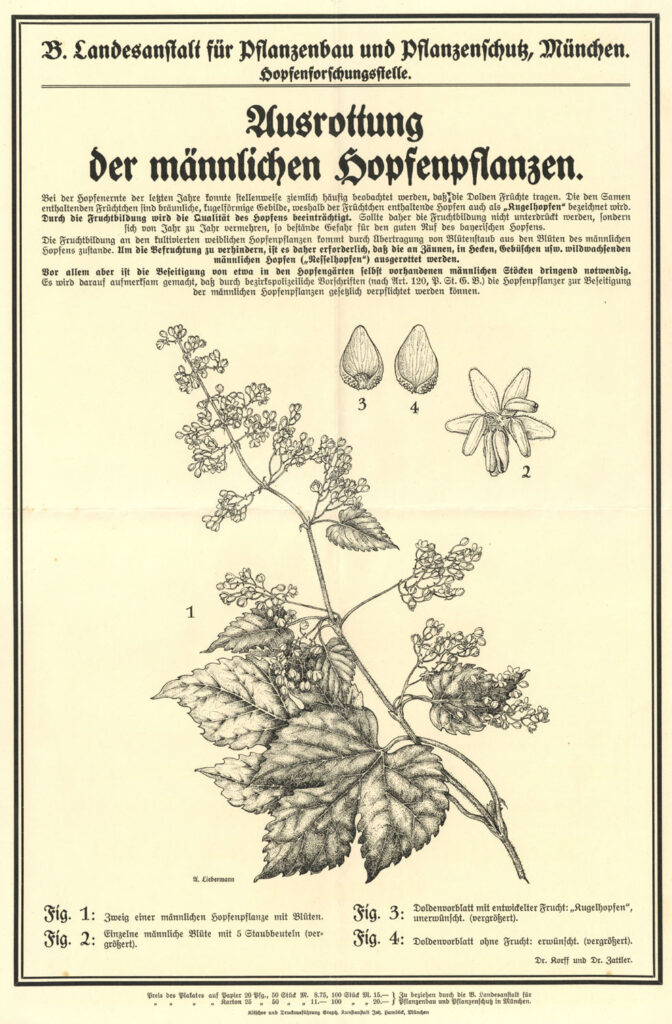

What was actually conceived as a scientific discourse increasingly turned into an economic policy issue. With their pro-male arguments, the British were also sending clear signals to the hop industry on the mainland. After all, they did not want to have their traditional culture of cultivation so easily denigrated. In Germany, a campaign had been underway since the end of the 19th century to radically combat male hops. As early as 1870, garden inspector Hannemann in Proskau, Silesia, had remarked that hops with seeds gave beer a “disgustingly bitter taste.” In addition, brewers and traders were increasingly refusing to pay for the superfluous higher weight of seed hops.

There was unanimous agreement among those responsible for German hop production – action had to be taken now. For good reason. The gold-rush atmosphere of the mid-19th century was gone, and German hop growing was deep in crisis. If the brewery clientele was to be paid reasonably reasonable prices, it had to be the very best quality. And it was decided that fertilized hops did not bear this seal of quality.

The Belgian Minister of Agriculture set a good example. As early as 1887, he passed a law stating that no more male hops could be planted in hop gardens. The Germans followed suit. At the “Versuchs- und Lehranstalt für Brauerei” (Research and Teaching Institute for Brewing) in Berlin, Dr. Theodor Remy provided clear evidence that fertilized hops were of poorer quality than those that remained virgin. All the alleged advantages were refuted. Seed hops not only had worse bittering values, but also the spindle proportions in the umbel were significantly higher, the color was paler, the appearance more fluttery. Above all, Remy dispelled once and for all the opinion that fertilized hops yield more. In weight and size, yes, but not at all in relation to the lupulin content.

A pest like the aphid, there is no pardon: extermination!

There was a direct response to Remy’s research. The Hallertau district of Pfaffenhofen a. Ilm took the lead and issued a “district police regulation for the destruction of wild hops” as early as 1901. What was actually meant was “destruction of male hops.” Other growing districts followed suit in the years that followed. The regulations were renewed several times until they finally culminated in the 1956 ordinance mentioned above. It is doubtful whether the hop growers followed this call with all due care. At any rate, the severity with which penalties were threatened in the event of violations suggests that this was the case.

Conclusion

Today, no (German) hop grower doubts the sense of these measures. Hops are considered to be a plant “which is its own enemy with regard to the use introduced by man”. If man has his way. In hop-growing regions today, male hops as well as wild hops should really only be found in research institutes such as the one in Hüll near Wolnzach. There, they are used for breeding new varieties, for example. In reality, however, the hops are not impressed by all the regulations and all the care. It can still be found in nearby floodplains and riverine landscapes, for example on the Danube, or in the bushes at the edges of forests. And especially in places where hops were once native centuries ago, you don’t have to look far for cultivated hop plants that have been released into the wild. Anyone who finds them is welcome to contact the Hüll hop researchers.