The 1952 Hop Grower Directory

A special source on the history of farms and hops

by Christoph Pinzl

The National Socialists had been in power for barely a month when, in February 1933, they issued a special “Ordinance on the Regulation of Cultivation Area.” One of the key provisions was that, with immediate effect, it should be determined each year “the maximum area that may be cultivated with hops in the following growing year.” And secondly, that all hop growers were obliged to provide precise information about how much hops they were growing. In practice, this meant that government officials turned up at every hop farm, took a close look at every hop garden, counted every single hop plant and, in case of doubt, also demanded access to the hop farmer’s accounts. The result of this count was then published with the name and place of residence of the hop grower in the local list of the respective municipality. It was publicly available for everyone to see at the town hall. As the icing on the cake, a metal sign was nailed to each hop garden, on which the name of the hop farmer and the approved number of hop vines could be seen from afar. Anyone who grew more than was stated on the sign had their vines cut down by the inspectors without further ado. It remains to be seen to what extent the right contacts in the party headquarters or similar had a say in what really happened in the hop gardens.

Sign for area quota allocation, ca. 1940. Alois Eibel from Gosseltshausen (Hallertau) was allowed to cultivate a maximum of 400 hop crowns on 0.08 hectares of land. The sign hung at the beginning of the hop garden.

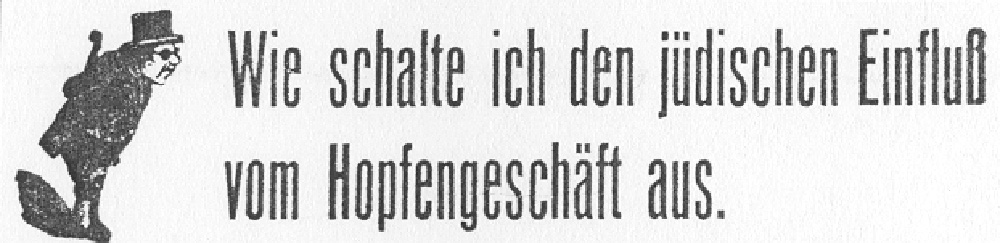

In any case, it was the opposite of a free market economy. For a long time, this had had a decisive influence on hop growing throughout Germany. Sometimes this was beneficial (when the market was good and prices rose), but often it had disastrous consequences: when the supply of hops far exceeded demand, prices collapsed and many hop growers had to give up. The latter was more the norm after the end of World War I in 1918. In Nazi ideology, however, these uncontrolled ups and downs of the hop market were not due to economic rules, but to the alleged influence of devious hop traders, which for right-wing ideologues naturally meant Jewish traders. For the anti-Semitic worldview of the new rulers, the new regulation of the hop market was therefore less a help to hop growers than the beginning of a systematic displacement of Jewish hop traders from the market. It didn’t matter whether the hop farmers liked it or not. Publicly available information about their own cultivation areas was a nightmare for every hop grower, regardless of whether they agreed with the regulation or not. Data protection was still a foreign concept at that time.

Interestingly, this regulation on cultivation areas remained in place even after the end of the Nazi regime in 1945 – until 1958! Even after the end of the war, the area regulation was not inconvenient for the growers’ association. After all, they wanted to prevent the former wild ups and downs of hop prices, the famous “hop roulette,” by any means necessary. Even if it meant adopting the guidelines of the former regime.

An interesting by-product of these circumstances was the 1952 hop grower directory. “In response to popular demand from various circles, especially from hop trading circles,” the Hop Growers’ Association decided to publish this register. It listed all hop farms in Germany, divided by growing regions and then by localities. Each farm was listed with its name, house number, and the area under hop cultivation. As mentioned, data protection was an unknown concept at the time. The directory was ultimately published in two volumes: Volume 1 contained only the hop growers of the Hallertau region, while Volume 2 covered all other areas that were active at the time: Spalt, Hersbruck, Jura, Tettnang, Rottenburg-Herrenberg-Weilderstadt, Baden, and Rheinpfalz.

Anti-Semitic advertisement from a daily newspaper, around 1935.

It is doubtful whether the fact that their business circumstances were laid out so openly and visibly for everyone to see really corresponded to the “general wish” of every hop farmer. The special handling of the sales prices for the books did the rest to ensure that the hop growers did not necessarily start cheering about the work. The directory cost a hefty 45 DM when it was published at the beginning of 1952 – per volume, mind you. At the time, that was half the monthly salary of a secretary in Munich. Apparently, this pricing policy was not really well received either. In any case, by May the price had fallen to 39 DM and by the beginning of October 1952 to 32 DM, which was still a hefty sum. How well or poorly the directory actually sold is not known, although the Hopfen-Rundschau claimed that it had been “enthusiastically received everywhere.” In any case, advertisements for the books appeared month after month for three whole years until the end of 1954 in the association’s magazine. By September 1953, the price had fallen to just 15 DM.

Whoever was really “enthusiastic” at the time, anyone who is interested in hop history today will be. This includes local historians, family researchers, and farm historians. For many hop growers today, this is the only way to get a relatively straightforward impression of the former size of their parents’ or grandparents’ farms and the associated infrastructure.

It gets really exciting when you start analyzing the data in larger units. Even if the books don’t contain much more than names, places, and area data. We have digitized the entire list of growers and used the appropriate software to pick out a few things in more detail.

According to this, in 1952 there were still 14,082 farms throughout Germany, i.e., hop farmers, families who lived from or at least with hop growing. Of these, there were 7,297 entries for the Hallertau region in 887 different localities, followed by the Spalt region with 1,907 growers in 135 localities and the Hersbruck Mountains with 1,851 farms in 227 localities. In Wolnzach alone, there were still 201 hop farmers active. However, the Hallertau hop metropolis was not even the German leader: at that time, there were still 250 farms in the town of Spalt. Next came Au i.d. Hallertau with 161 and then – surprise, surprise – Hambrücken (Karlsruhe district) in what was then the Baden growing region (149 growers), once even the site of the (allegedly…) largest hop kiln in Germany. In addition to expected hop centers such as Mainburg or Siegenburg (both Hallertau) or Großweingarten (Spalt), each with several dozen growers, there were also place names such as Unterjettingen in the Württemberg district of Böblingen (96 growers), Tailfingen in the Swabian Alb (80), and Kapellen-Drusweiler on the Southern Wine Route in the new federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate (72) were also high on the list.

The hop grower directory from 1952, Volume 1: Hallertau.

In terms of area, however, Wolnzach was again in the lead with 182 hectares of hops, ahead of Spalt with 140 hectares and Au i.d. Hallertau with 123 hectares. This brings to mind a frequently described finding: that Spalt farms tended to be smaller or cultivated less hops than their Hallertau competitors. This was already the case in the 19th century and is considered by economic historians to be one of the main reasons why Hallertau was able to prevail over the Spalt region on the hop market in the long term. Incidentally, in 1905, Spalt still had 270 hectares and Wolnzach 262 hectares.

The largest German hop grower at the time was Otto Höfter, who lived in Neuhausen in the Hallertau region and had 15.60 hectares of hops, followed by Paul Münsterer in Mainburg, the Barthhof hop farm near Wolnzach, and the Wittmann family in Siegenburg. Only then did the Steiner farm in Siggenweiler near Tettnang come into play as a business outside the Hallertau region. With a few exceptions from Tettnang, Spalt, and Hersbruck, the 200 largest German hop farmers all lived in the Hallertau region, where “large” at that time meant between 2 ½ and 7 hectares. Almost 4,000 farms in Germany, or just around 30%, cultivated only 0.2 hectares of hops or less. According to the hop growing textbook of the time, this meant around 800-900 hop poles, with some hop growers in the Hersbruck Mountains and Baden owning as few as 100 plants. This makes it clear that even back then, many hop growers in Germany could no longer make a living from green gold alone.

The 1952 hop grower directory, volume 2: Spalt, Hersbruck Mountains, Jura, Tettnang, Rottenburg-Herrenberg-Weilderstadt, Baden, Rhine Palatinate.

Incidentally, it was not uncommon for women to own farms. However, they were often not listed under their actual names, but as “Anton Graf Widow” or “Schlotterbeck Adolf Wdw.” This, too, is a reflection of the times, times when women were still completely subordinate to their husbands in legal terms. It is also a sad reminder that World War II had ended just seven years earlier and many farm owners had not returned home.

If necessary, many insights could be filtered out of the data in the planters’ register. For example, the interesting fact that Josef was the most popular first name among German hop farmers, closely followed by Johann and, at a slight distance, Georg. However, this was not the case in Spalt, where Johann was far ahead, unlike in Baden with Wilhelm or in the Rhine Palatinate with Karl. You can also find such melodious names as Arsatius, Agathon, and Agapitus. Whatever conclusions you may draw from this, more or less meaningful.

Today, only a tenth of the former number of growers remain in the Hallertau region. In the former hop metropolises of Wolnzach and Spalt, only two and three growers respectively are still flying the flag. In Baden, the Rhine Palatinate, and around Rottenburg am Neckar, hops have not been planted for a long time. The Jura and Hersbruck Mountains are now officially part of the Hallertau. In the entire Spalt area, 43 growers are currently still cultivating hops.

Excerpt from volume 1. The entries for Wolnzach alone filled several pages.

If you would like to take a first look at the information in the grower directory, you can do so directly in the permanent exhibition of our museum. In our “interactive map,” you can call up data from 1952 for individual locations, whether your own farm, your neighbor’s, or somewhere else entirely, as you wish.

(written with the help of NI*)

*Natural Intelligenc