Slaughter bowl with Maid Himmelstoß

In the past, the hop harvest was often accompanied by outbreaks of violence.

By Christoph Pinzl

Brave estimates put the number at 200,000. A more realistic figure is probably 120,000, or 150,000 at most. Hop pickers. Hop pickers who, until the 1960s, populated, not to say overpopulated, the Hallertau region for several weeks every year from the end of August. Because however many actually came – total numbers were never recorded – there were more people than lived here at the time. Old hop farmers fondly remember the “good old days” with tears in their eyes, singing hearty songs, tasty food, pretty pickers, cheering, hustle and bustle, and merriment. The old pickers, on the other hand, were less inclined to reminisce, as it was not a thirst for adventure that had driven them to the hop-growing region, but rather the harshness and poverty of their everyday lives, whether in the big city or in a “structurally weak” area like the Bavarian Forest. They were used to struggling to get by. However, this could also mean quite literally that men and women didn’t put up with anything, often combined with a very high sensitivity when it came to insults or protecting what they had.

With so many people coming together in such close quarters, conflicts were inevitable.

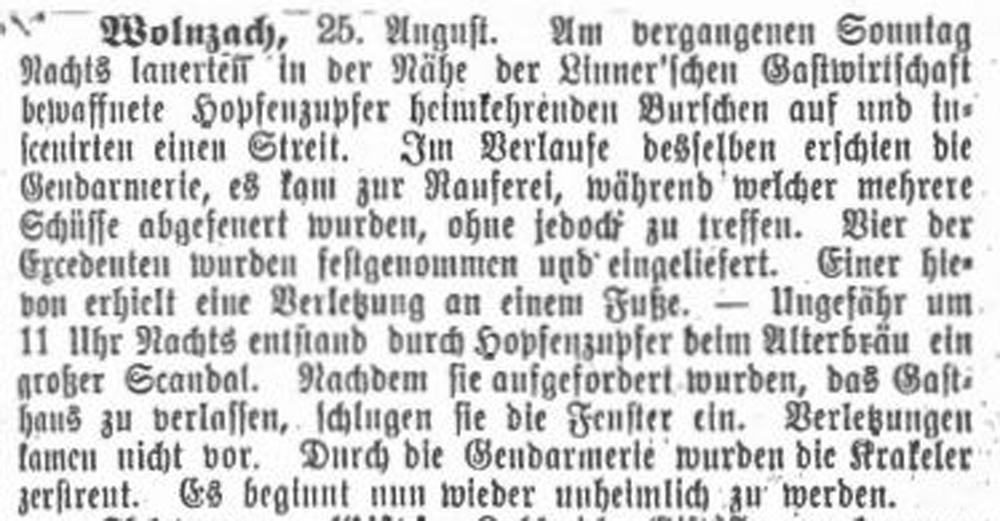

This meant that during the hop harvest, things could get quite rough, especially in the evenings or at the end of the harvest, when a beer or two had taken effect and strangers and locals met on equal terms. Hop picking on a large scale in the Hallertau region is likely to have begun at the earliest in the early 19th century. Before that, local workers – farmhands, maids, neighbors, children – did most of the picking without outside help. In the evenings after work in the stables, at home in the living room or sitting in front of the barn by the dim light of a lamp. Not that much hops were grown back then. It was not until around 1850 that the harvest became so large, at least for larger farmers, that they had to hire external harvesters. But it did not take long before the Hallertau gained a somewhat dubious reputation during harvest time. As a precaution, the police force was increased. The farmers themselves tried to create a good working atmosphere with clever measures to reduce the likelihood of friction. The food had to be tasty and plentiful, men and women should sleep separately if possible, and work continued late into the evening until everyone was hopefully exhausted. Real wages were only paid at the end of the harvest so that not too much of the earnings ended up at the innkeeper’s bar in the evening and clouded the senses. And yet. A report in the Wolnzacher Anzeiger newspaper on August 25, 1903, about the first incidents in Wolnzach ended with the grim sentence: “It is now beginning to get eerie again.”

It is now beginning to get eerie again.

Strangely enough, many reporters felt compelled to write about such outbreaks of violence as if they were a performance from a bawdy peasant farce. As if the brawls were revealing the robust Bavarian soul, which simply could not be tamed. Ultimately, it was all just good fun, which newspaper readers could smile about the next morning. A few days after the above report, there was already news of the next dispute, this time in Gebrontshausen, between pickers and the village lads, “whereby the pickers were thoroughly beaten up. They are said to have remarked that they had never been beaten like this before by the guys from Gebrontshausen.” Ah, the Gebrontshausen boys, well then. “The instigator was a woman,” the author added. With all their prejudices confirmed, the local readers could sit back and enjoy the story. Elsewhere, it was reported that “the pubs were littered with broken chairs and chair legs and smashed beer mugs, and broken arms and holes in heads were not uncommon, although the hardness of the thick skulls was usually greater than that of the stone mugs.” Ho ho.

The mood after the hop harvest is still great. However, that could change quickly. Neuhausen (Hallertau), around 1950.

In 1956, a writer with the clever pseudonym Dr. Gustl Bierling concocted a kind of Bavarian ballad with a dash of situational comedy from a street fight between pickers and farmhands in Au i.d. Hallertau. There were “storms of laughter” in the courtroom where the participants later had to answer for their actions, which Bierling reported smugly. Eight hop pickers from Straubing felt insulted when one of the village lads from Au got too close to “Maid Himmelstoß” (Miss Heavenly Bump), whereby reporter Bierling – at that time still completely politically incorrect – couldn’t resist describing her name as “promising.” This naturally led to a brawl, with all the necessary ingredients such as knives, which ended up in the thigh of a farmer “with the ominous name Stitch,” beer glasses that were “hurled by delicate pickers’ hands” into faces, and a bawling innkeeper who threatened to “turn all hop pickers into white sausage.” And so it went on: with the pitchfork-wielding hop picker Luise-Thusnelda, sledgehammers landing on the backs of farmhands who didn’t wake up until the next day in the hospital, two fence slats on one head, and butcher knives, which the judge, surely a man straight out of the Royal Bavarian District Court, humorously described as “a very healthy knife”: “Heartfelt merriment in the courtroom.”

Intergender interactions seem to have been a frequent cause of disputes, at least according to contemporary reports.

Regardless of the fact that some of those involved in the only seemingly amusing riot in Au had to serve long prison sentences, such “pickers battles” read much less amusing elsewhere. The weekly and bi-monthly reports of the Hallertau district offices struck a completely different tone when it came to the clashes during the hop harvest. The descriptions of the bailiffs and police officers sometimes sound so drastic that they are reminiscent of the scripts of gruesome horror films, which is why they will not be quoted in detail here. In any case, the reports were overflowing with “breaches of the peace,” “hop picker revolts,” and “picking wars,” sometimes with several incidents in a single day. These were often accompanied by devastated restaurants, taverns set ablaze, life-threatening injuries, and ultimately even deaths. In 1928, when the mayor of Niederhornbach near Pfeffenhausen tried to intervene in a dispute between hop pickers, he was stabbed in the abdomen and died shortly afterwards in the guesthouse. Elsewhere, a landlord who had also been stabbed in the stomach died miserably from his injuries days later. In 1912, after a hop feast in his inn, the innkeeper of Enzelhausen could only defend himself against the drunken hop pickers by firing uncontrolled shots into the crowd, whereby, astonishingly, only life-threatening injuries were reported, but no deaths. In 1903, a battle that had moved from Appersdorf to Elsendorf escalated so badly that only the 4th Battery of the 8th Field Artillery Regiment, which happened to be conducting maneuvers nearby, was able to restore peace. Some of the ringleaders ended up in prison for years.

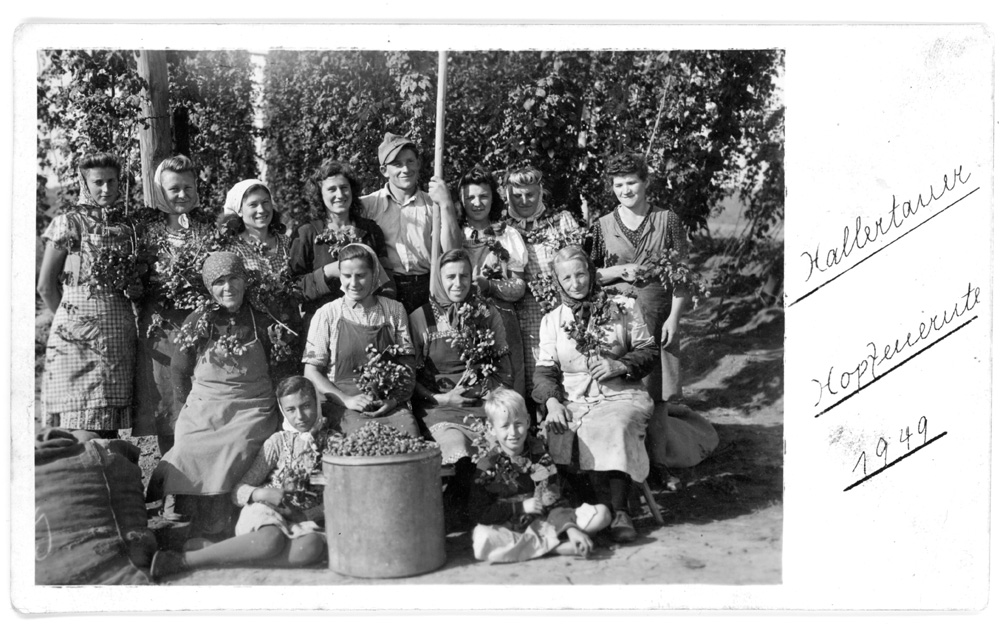

After World War II, it was mainly women who came to harvest hops. This was certainly one reason why violence during the harvest declined.

After World War II, the conflicts decreased significantly. Fortunately, incidents such as the “Maid Himmelstoß” episode described above became the exception. This was certainly also due to the fact that the origin of the harvest workers had changed considerably in the meantime. Even before, during, but especially in the years immediately after the war, almost only women came to harvest hops, often with small children in tow. Many were displaced persons from Eastern Europe who were happy to be able to integrate as inconspicuously as possible into their new home. Of course, conflicts continued to arise where so many people had to get along in such close quarters, but they were no longer fought with knives, pitchforks, and sledgehammers. It was good that the “bad old days” were over.